Political campaigns worldwide are increasingly using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to gain an edge. But how does this affect our democratic processes? In a new study with Adrian Rauchfleisch and Alexander Wuttke, and I show what the American public thinks about AI use in elections.

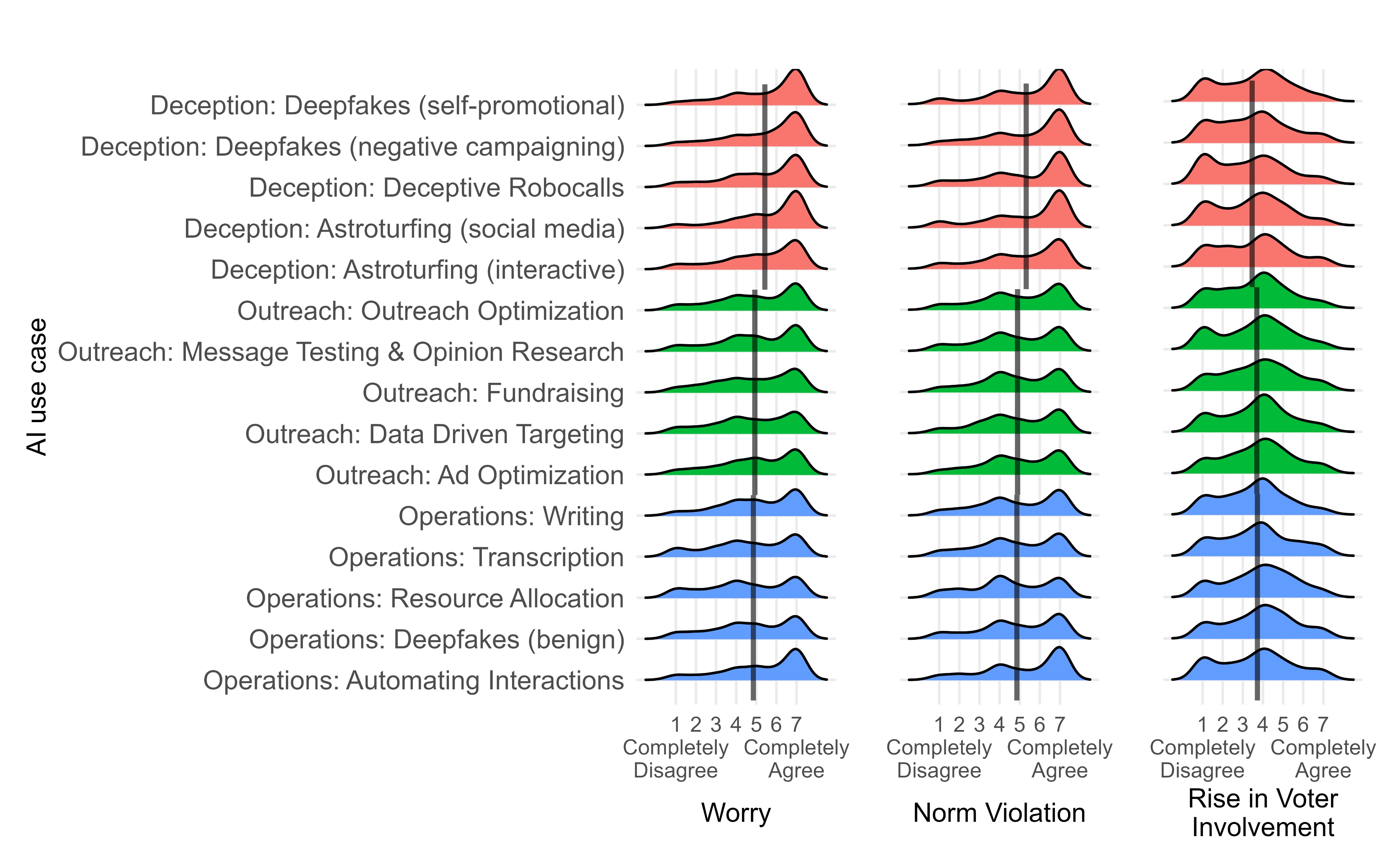

We propose a framework that categorizes AI’s electoral uses into three main areas: campaign operations, voter outreach, and deception. Each of these has different implications and raises unique concerns.

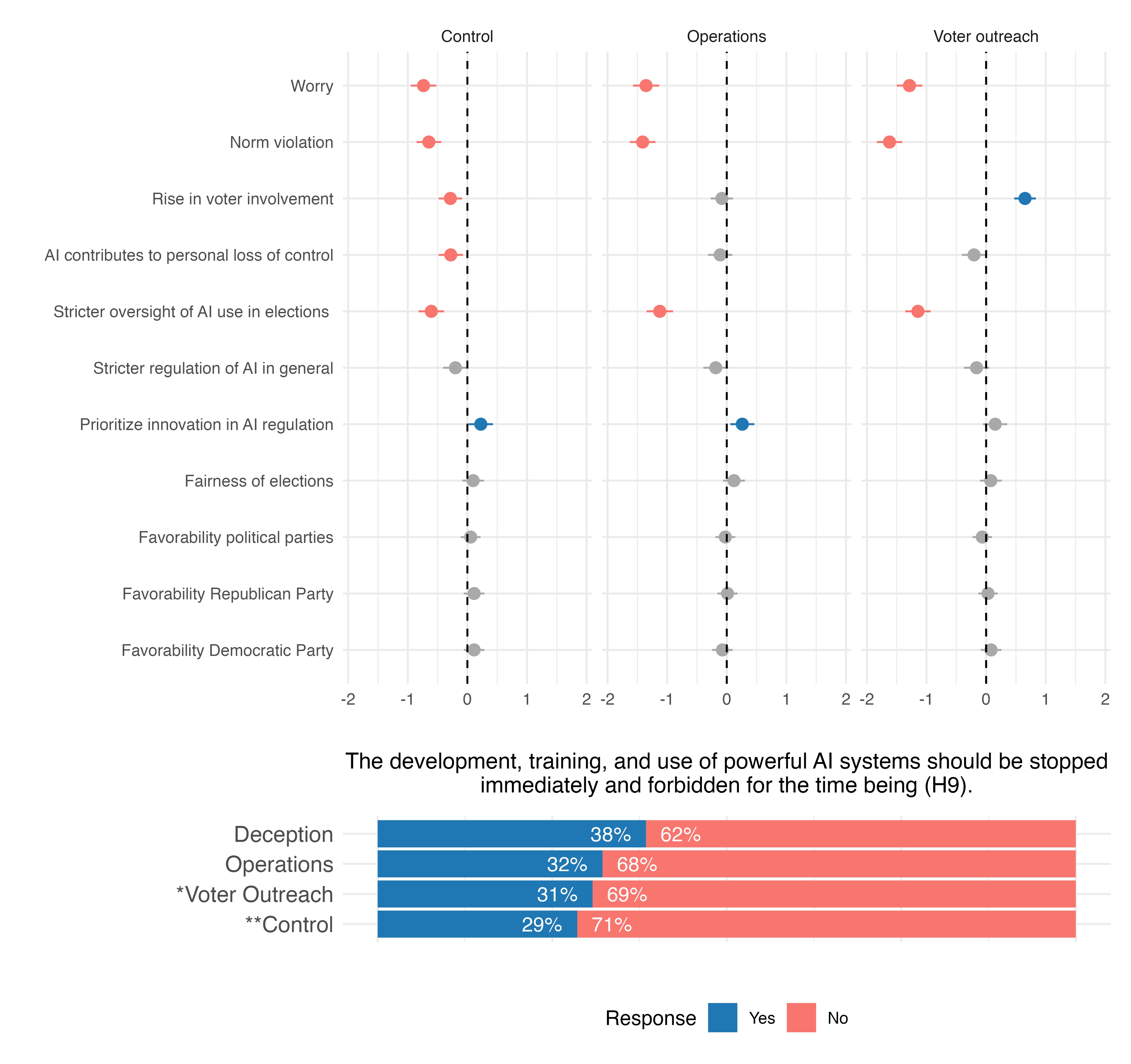

Public Perception: Through a representative survey and two survey experiments (n=7,635), the study shows that while people generally view AI’s role in elections negatively, they are particularly opposed to deceptive AI practices.

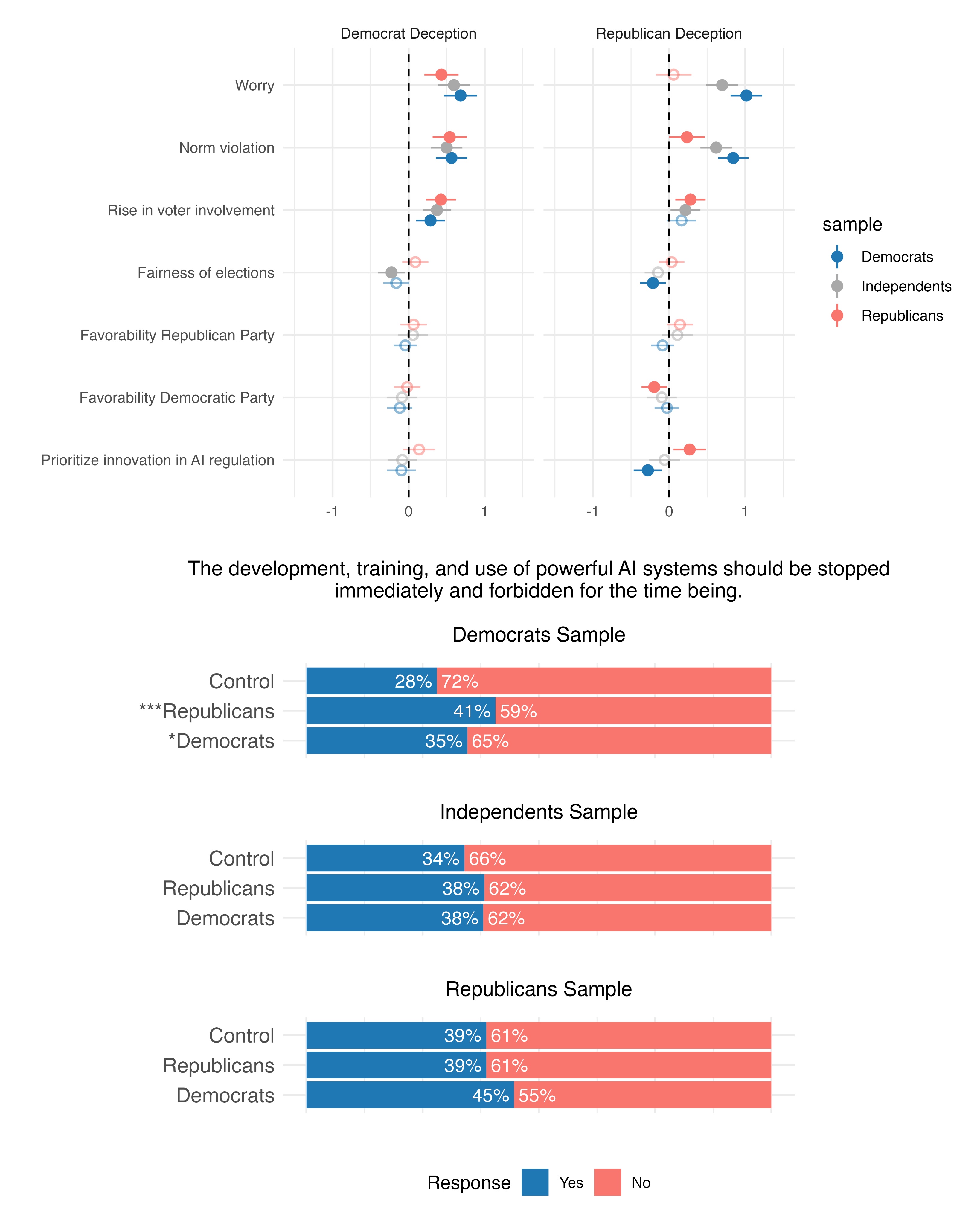

Deceptive uses of AI, such as deepfakes or misinformation, are not only seen as clear norm violations by campaigns but also increase public support for banning AI altogether. This is not true for AI use for campaign operations or voter outreach.

But despite the strong public disapproval of deceptive AI use, our study finds that these tactics don’t significantly harm the political parties that use them. This creates a troubling misalignment between public opinion and political incentives.

We can’t rely on public opinion alone to curb AI misuse in elections. There’s a critical need for public and regulatory oversight to monitor and control AI’s electoral use. At the same time regulation must be nuanced to account for the diverse applications of AI.

As AI becomes more embedded in political campaigns and everyday party operations, understanding and regulating its use is crucial. It is especially important not to paint all AI use with the same broad brush.

Some AI uses could be democratically helpful, like enabling resource-strapped campaigns to compete. But fears of AI-enabled deception can overshadow these benefits, potentially stifling positive uses. Thus, discussing AI in elections requires considering its full spectrum.

Abstract: All over the world, political parties, politicians, and campaigns explore how Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help them win elections. However, the effects of these activities are unknown. We propose a framework for assessing AI’s impact on elections by considering its application in various campaigning tasks. The electoral uses of AI vary widely, carrying different levels of concern and need for regulatory oversight. To account for this diversity, we group AI-enabled campaigning uses into three categories — campaign operations, voter outreach, and deception. Using this framework, we provide the first systematic evidence from a preregistered representative survey and two preregistered experiments (n=7,635) on how Americans think about AI in elections and the effects of specific campaigning choices. We provide three significant findings. 1) the public distinguishes between different AI uses in elections, seeing AI uses predominantly negative but objecting most strongly to deceptive uses; 2) deceptive AI practices can have adverse effects on relevant attitudes and strengthen public support for stopping AI development; 3) Although deceptive electoral uses of AI are intensely disliked, they do not result in substantial favorability penalties for the parties involved. There is a misalignment of incentives for deceptive practices and their externalities. We cannot count on public opinion to provide strong enough incentives for parties to forgo tactical advantages from AI-enabled deception. There is a need for regulatory oversight and systematic outside monitoring of electoral uses of AI. Still, regulators should account for the diversity of AI uses and not completely disincentivize their electoral use.